- Home

- Nasreen Munni Kabir

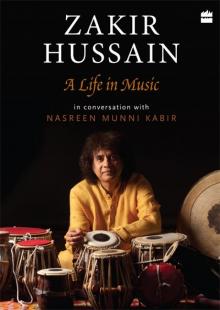

Zakir Hussain

Zakir Hussain Read online

ZAKIR HUSSAIN

A Life in Music

In Conversation with Nasreen Munni Kabir

HarperCollins Publishers India

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Book

About the Author

Copyright

Introduction

In the mid-1980s, I happened to spot Zakir Hussain in a well-known store in Bombay’s Taj Mahal Hotel. I had not met him formally before that day, but he appeared to be an approachable kind of person despite being a world-famous musician. However, greeting him without any introduction seemed an invasion of his privacy. And, after all, what could I say? That he played the tabla brilliantly, his dexterity and skill were magical to watch on stage, that I loved his music? Instead, I discreetly followed his movements around the shop from the corner of my eye, but just as he was about to leave the store, he gave me a lovely smile and said hello. Even though some forty years have passed since that random encounter, I can still recall his warmth and friendliness.

Since that time, and in many cities of the world, I have seen Zakir Hussain perform with a variety of musicians, both Indian and international. His extraordinary playing and the extreme sense of rigour that he brings to his art are clearly manifest. Among the many cherished evenings with Zakir’s music, a most memorable one was seeing the path-breaking Shakti on stage in the 1970s. The Shakti sound was so exhilarating that I felt I was on an airport runway and my heart was about to take off.

The training that Zakir Hussain received under his father, the extraordinary Allarakha, started at a very young age, but it was not long before he began to receive acclaim for his own sound and style. As a musician, Zakir Hussain was considered a child prodigy; today he is considered a genius. Despite the international reputation and huge following that he now has, he wears his fame lightly. He remains a man of tehzeeb and humility. Zakir has broken many records and won many awards, but is always the first to credit the ‘Holy Trinity’ of tabla players, Pandit Samta Prasad, Pandit Kishan Maharaj and his father, for their groundbreaking contribution to music, and for the fact that they elevated the very status of the tabla in the first place.

Having worked on a number of conversation-based books with the leading names of Indian cinema, I felt bold enough to try and approach this gifted musician with the idea of doing a similar book. Although I am neither a musicologist nor a music expert, I believe the discipline and passion that drive many artists to keep growing, whether as film-makers or musicians, are much the same. And so I convinced myself that even if my questions were not those of an expert, Zakir Hussain’s answers would help music lovers like myself to better understand his music and to discover the path his life has taken. There is so much to learn from Zakir Hussain. He is a musician who has for over six decades practised the art of the tabla, playing not only with four generations of master musicians of India, but accompanying many greats from the world of Western classical, rock and jazz.

I finally plucked up the courage to ask my friends Ayesha Sayani (affectionately known as Pooh) and Sumantra Ghosal if they could introduce us. I had seen Sumantra’s wonderful documentary, The Speaking Hand: Zakir Hussain and the Art of the Indian Drum, and knew that if they believed I could do justice to the subject, they would encourage me, and if not, I would be dissuaded. Ayesha, who had read some of my books, was instantly enthusiastic and said the best way forward was that she first introduce me by email, and that I then send a formal letter outlining the idea for a book and requesting to meet him on his next visit to Bombay.

It was entirely through the generosity of Ayesha Sayani and Sumantra Ghosal that, in January 2016, the four of us met. Since the meeting took place after the lunch hour at a well-known Bombay restaurant, we had the restaurant to ourselves. Zakir patiently heard me out as I explained that my area of research was cinema and not music, to which he said, ‘So this would be a leap of faith? In any case, I do not want a how-to-play-the-tabla book.’ Our meeting ended with him saying that he’d get back to me once he had read some of my books.

A few weeks later, Zakir phoned and very matter-of-factly gave me the go-ahead. I was absolutely delighted and immediately called Ayesha Sayani to share the news. I will always be grateful to Ayesha and Sumantra for encouraging me throughout, and believing that the book would happen. I extend my thanks to them again here.

For the following two years, between 2016 and August 2017, Zakir Hussain and I met in various cities—Bombay, Pune, London and even Antwerp. Each of our fifteen sessions lasted for about two hours. Our conversations, mostly in English, peppered with Hindi/Urdu, were recorded on a small digital recorder and then transcribed. As many of the events we talked about date to the period prior to the renaming of Bombay to Mumbai, Calcutta to Kolkata and Madras to Chennai, I have used the original city names for consistency.

Working around the clock, Zakir also travels to every corner of the globe and gives about 200 concerts a year, but despite the pressure on his time, when he answered my questions he gave full and thoughtful attention. In London, we met at whichever hotel he happened to be staying, and in Bombay, we talked in his home in Simla House—a place that has been witness to over fifty years of Qureshi family history. In the course of our many conversations, his vast knowledge of every kind of music was evident, and his understanding of form and tradition, multilayered and insightful.

Zakir has a very quick and analytic mind. With his intuitive and instant reading of the musical expression of the artist with whom he is playing, it is no wonder that he can so easily accompany many different kinds of musicians. His years of teaching tabla in America and interacting with music students from all over the world is perhaps why he is also able to explain difficult musical concepts in a clear and accessible way. In fact, he can converse on any subject and has a natural flow of ideas with a phenomenal memory for anecdotes and incidents—many fascinating stories are recorded here as he remembers his encounters with the great names in music.

Zakir Hussain is noticeably personable and friendly, but is also someone who likes doing things in a certain order—so if I happened to rush him, he would stop me and slow the pace down. The perfectionist in him would also lose patience with any errors that he would spot in our working drafts. It was important to him that things were ‘just so’.

This book has taken over two years to complete, and I hope it will serve as an introduction to an intelligent and thoughtful man who happens to be a truly exceptional musician. I believe only a multi-volume biography can even start to cover the many aspects of his life’s work and I hope this book is a step towards this possibility. Getting to know Zakir Hussain through the process of writing this book and to learn about music from a musician so gifted and yet who still has a sense of openness to take that leap of faith has been an immense privilege.

NASREEN MUNNI KABIR

Zakir Hussain (ZH): From the very start we were somehow tied together—me and my dad. I was always very attached to him. As a child, I remember I used to stay up late into the night and refuse to sleep until he came home, and only then did I go to bed.

Around the time that I was born, my father was suffering from a heart ailment and was extremely unwell. Someone had told my mother that I was an unlucky child because my birth coincided with this most distressing time for the family. My father, whom we called Abba, was so critically ill at that time that many of his colleagues and friends came to say a last goodbye. This included Raj Kapoor, Nargis and Ashok Kumar who starred in Bewafa, a film for which Abba had composed the music.

My mother did not breastfeed me when I was brought home. She really believed that I was unlucky, and so a close friend of

the family who lived near us in the mohalla of the Mahim dargah [neighbourhood of the shrine of the saint Hazrat Makhdoom Ali Shah] looked after me. I sadly don’t remember the name of this kind lady, but she became a sort of surrogate mother to me for the first few weeks. You can imagine this was out of the ordinary because the eldest son in an Indian family is usually treated like a prince.

I was told that a holy man called Gyani Baba appeared at our door soon after my birth. He called out to my mother by her name, Bavi Begum. No one had a clue how he happened to know her name, but somehow he did. My mother went out to meet him and Gyani Baba looked at her and said: ‘You have a son. The next four years are very dangerous for him, so look after him well. He’ll save your husband. Name the child Zakir Hussain.’

Hussain is not the family name. My surname should have been either Qureshi or Allarakha Qureshi. But Gyani Baba insisted that I must be called Zakir Hussain; he also said that I should become a fakir of Hazrat Imam Hussain, the grandson of the Prophet.

One of the duties of a fakir is to go to seven houses during Muharram and ask for alms. The purpose of this is to learn humility. The fakir must then give whatever he has received to those poorer than himself. So, as a toddler, during Muharram, my mother would dress me in a green kurta, give me a jhola to carry and we’d go from house to house in our neighbourhood asking for alms. People gave me a little money or some sweets. Whatever I was given went straight to the mosque or to the Mahim shrine. When I was older, I continued this practice during all the years that I lived in India. Even when we moved to Nepean Sea Road in the 1960s, I would go back to Mahim during Muharram, and when I moved away to America, for many years, Amma continued this penance in my place.

Another thing that Gyani Baba told Amma was to watch over me, and sure enough, for the first four years of my life, I kept falling sick. I would accidentally drink kerosene, or my body would be covered with unexplained boils, or I would suddenly get a high fever, maybe it was typhoid or something. But the interesting thing was, the worse that I got, the better my father became. As Gyani Baba had predicted, four years later Abba was fit and well, and by that time, I was in good health too.

So that’s how I got my name.

Nasreen Munni Kabir (NMK): And ‘Zakir’ means? The one who remembers?

ZH: It can mean the one who remembers, or the one who does zikr, which is a form of devotion that involves rhythmically repeating Allah’s name, or repeating a mantra-like chant. Zikr is part of the Sufi tradition, and the whirling dervishes, for example, also practise zikr to attain God. So Zakir is the one who does zikr—my name means something like that.

NMK: I did not know the story behind your naming. What an intriguing start to a hugely eventful life. I am just wondering if Gyani Baba was a Muslim or a Hindu.

ZH: He was not a Muslim. In later years, I asked my elder sister Khurshid Apa about him and she said all she knew was that he cooked his own food and carried it around with him because he did not want to eat food made by another hand.

In those days, it did not matter if Gyani Baba was a Muslim or a Hindu. I guess even being Sunni or Shia did not really matter—perhaps for the hierarchy it did matter—but for most people it didn’t. Many musicians followed Shia Islam and in those days, many worked among baijis in kothas, so they would not perform during Muharram.

One Muharram, I remember going to a majlis [a gathering to remember Hazrat Imam Hussain] with my father to Bade Ghulam Ali Khansahib’s house. There were many musicians there—it was something like the salons in old Europe where a candle was passed to each artist who then recited a poem or sang—here a paan-daan (usually an ornamental silver paan box) was passed around. Whether the paan-daan was passed to an instrumentalist or a vocalist, once it was placed in front of the musician, he would sing a ‘naat’. These devotional songs only had a few verses, and since the singers would melodically embellish the naats of their choice, each performance would last about twenty minutes and then the paan-daan would move on to the next person and the next. It was very interesting to watch.

NMK: Do you think a recording of those evenings exists? The singing must have been beautiful.

ZH: I don’t know. Most musicians did not own a tape recorder in those days. In fact, we didn’t either, not until the mid-1960s when my father brought a Philips tape recorder from America. In any case, I doubt if they would have let the majlis be recorded because it was not a performance. They sang for God.

As for me, I could not sing a whole naat, but I could say a few lines. I was just a little kid, a spectator, who was sitting around. Abba would sing and later he composed some naats in films that had a Muslim setting.

NMK: What is your first memory? I mean from your childhood.

ZH: A first memory as a child? There are quite a few things I remember. It’s hard to think of the very first memory.[long pause] Our first home in Mahim was a little room. I was about two or three years old. I remember our tiny kitchen very clearly. It wasn’t a kitchen-kitchen. You walked through the door into the room and you could see a small cemented square area that had a drain—there was a four-foot wall cordoning it off, and on the other side of the wall, a kerosene stove was placed on the floor. Amma had lined up pots and pans against the wall and she would sit on what was called a ‘patara’—a very low wooden stool with short legs—while she cut vegetables. To get the kerosene stove going, Amma would have to use an air pump and then she’d cook on that stove. I remember taking a cooking pot from that tiny kitchen, turning it over and drumming on it. Yeah!

Another memory that comes to mind was when I was about three and I saw Abba riding back and forth on the street on a bicycle. I thought that was cute! Here’s this ustad on a bicycle weaving his way up and down the neighbourhood. The cycle must have belonged to some student of his who happened to be visiting, and my father had probably decided on a whim to try riding it. Abba had a big grin on his face and everyone around him had even bigger grins on their faces. That’s a happy memory. [smiles]

NMK: Did your father lose his temper easily?

ZH: No, no. He was not an angry man. He was very calm. I never saw him get upset with his students either. If they messed up, he would say, ‘Dhat teri ki, kya hai?’ [Damn it! What’s wrong?] There was no screaming and shouting, none of that. He never hit me, except for once. I think I was about nine. He slapped me because I had broken my third finger while playing cricket. And that was a no-no as far as he was concerned. I was going to use those hands to play the tabla. When he slapped me, I had tears in my eyes and he didn’t like that, and so he gave me a hug and took me to the Sindhi chaat shop nearby and got me a plate of dahi batata puri. [smiles]

NMK: We were to start our conversations yesterday (20 May 2015), but we missed our first appointment. I knocked on your hotel door, but you didn’t hear me. You had just landed in London and when we spoke later, you said you had fallen asleep with your earphones on. What were you listening to?

ZH: Tomorrow I’m playing at the Royal Festival Hall with three Indian musicians and a group of Celtic musicians—some are from Scotland and others from Ireland and Brittany in France. I was listening to their music, so when I meet them today for rehearsals, I can say: ‘You remember that song you played? Well, the Indians have come up with this idea to go with that, shall we try it?’ That’s better than asking what we should play and then looking at each other in the hope that someone might suggest something.

When I play with different musicians, and sometimes it could be for the first time, it is important to know how they express themselves musically. To know what appeals to them in terms of tonality, or what kind of pitches they favour, so that I can bring a set of instruments to support those pitches and tones.

Say, if I’m going to play with a jazz band, I listen to their albums, read their interviews and familiarize myself with their music. It’s a way of showing respect and that I am not just arriving at the concert hall thinking: ‘Oh, I’m going to play with you, we’ll see what that’s like in

the dressing room.’

NMK: So you immerse yourself in their world of music. Have you always prepared to play with your fellow musicians in this way?

ZH: I am not playing an entirely fixed piece of music, but music that requires some spontaneity. Creating something new does not always happen on the spot, therefore understanding a musical style allows me to rearrange things a little, to mix and match. It’s like seeing a flower in a vase, and it looks good, but you know if you turned the flower, it could look just that bit different.

Being aware of musical styles is definitely prevalent in the jazz world in the West, the white world or the black world, or whatever you want to call it. You’ll find jazz musicians constantly listening to other musicians, especially if they are going to play music together.

NMK: One always thinks of jazz as improvisation, but you’re talking about researching. Improvising within a framework.

ZH: It is research because music is a conversation. And a proper conversation can only happen if you know each other well. If you’re just strangers, you say: ‘Hello, how are you?’ ‘I’m okay, thank you.’ That’s fine, but your connection won’t go very deep. And yes, it’s definitely within a framework. It has to be, otherwise we would be meandering along on the stage with no head or tail, without an idea of how to begin or end.

You’re asking me questions, but they’re not off the top of your head, you’ve prepared, you know how you want to begin each session. Our conversation may branch off into a zillion directions and that’s great, but there has to be some research and understanding. I think it’s a sign of respect for each other to have that.

NMK: Was research needed when you started to play with Indian musicians?

ZH: I was very lucky. From the age of seven, I sat on the stage with Abba whilst he played with so many greats. It was a lived experience for me, and it allowed me to absorb all that I had heard over the years.

Zakir Hussain

Zakir Hussain