- Home

- Nasreen Munni Kabir

Zakir Hussain Page 4

Zakir Hussain Read online

Page 4

NMK: Where was the family home in Mahim?

ZH: For the first three-and-a-half years of my life, we all lived in one room that had no toilet. We had to use the common toilets. It was a chawl. The building does not exist anymore.

In 1954, we managed to upgrade to a flat in Akram Terrace, which is behind the dargah in Mahim. Akram Terrace still exists. It was thanks to my mother who was very frugal that we could move from the chawl.

Amma could make one rupee go a long way and in those days one rupee did go a long way. She managed to pay the deposit and the rent on the Akram Terrace ground-floor flat. It had two medium-sized rooms on either side of a large living room. There was a small kitchen, a bathroom and toilet. That was our home till we moved to Simla House in the late 1960s—to this same flat where we’re now talking. Coming here was a big graduation.

NMK: How did your mother manage to buy this place?

ZH: It cost about 124,000 rupees, a fortune in the 1960s. All the money had to be paid in cash and upfront. Mortgages and bank loans were not possible and in those days it was all hard cash.

Amma had saved up as much as she could. Back then you could transfer your pagdi to another tenant, and if I remember right, she got about 55,000 rupees from the deposit of the Akram Terrace flat, but we were still short of some thousands. So Amma spoke to the session musicians that she knew and asked them to find me work playing the tabla for film music so that I could earn a little money. And so I ended up playing the tabla on many film songs—songs that were composed by a variety of music directors, including Naushad Sahib, Roshanji, and Madan Mohanji and there were others too. This was sometime in the mid-1960s. I was only a teenager. Whatever I earned was added to our savings, and Amma finally managed to buy this flat in Simla House. All this happened when my father was out of India on tour. He had left while we were still in Mahim and when he returned we were living on Nepean Sea Road. It must have been a shock for him to come back to an entirely new home.

I must admit those days are a blur now. For two months, I would go to school during the first half of the day, and the second half would find me in some recording studio. Some of my tabla player friends recognize my playing and try to jog my memory: ‘What about this song? And this? Is this you?’

I can’t remember the songs very well. There was Madan Mohanji’s music in Mera Saaya. S.D. Burman’s Guide and Dr Vidya. There were lots of films in production and I played alongside the session musicians, many were from Goa. There was Mr D’Costa, Mr Waghmare, Mr Fernandes, a Parsi guy called Guddi and of course young Kersi Lord. He passed away recently. There was also Lala Bhai, Sattar Bhai, Naidu the dholki player, Maruti Keer, Karim and Iqbal—they were great players of the tabla, dholak, dholki and various other drums. I remember we did not call the musicians by their first name because you showed respect.

Back then I think there were about four or five recording studios used for film music. There was the Bombay Sound Service, which was part of the Bombay Labs near the Portuguese Church in Dadar, and Mehboob Recording Studio was in Bandra. It had a big hall for musicians to sit and play. We also recorded at Famous and Film Center—both studios were in Tardeo. At Mohan Studio, they would record music on their sound stage after the day’s shoot had taken place. That’s why in the old days, they used to tell the musicians: ‘Set pe paisa milta hai’ [You’ll get paid on the set].

The sound engineers ran the recording studios. They were not brought in for a particular film. The in-house sound recordist at Bombay Sound Labs was B.N. Sharma. Minoo Katrak, the sound designer, mixer and recording engineer worked at Famous in Tardeo. They were very well known. The recording engineer Daman Sood came later.

Nowadays composers can sample everything. They have a big keyboard on which they have violins, violas, cellos, trumpets, the French horn, etc. Depending on the budget, the composer uses what’s on the sequencer. They call in singers who will record the song without the orchestra. The singers just have the sur [a pitch instrument] and based on their rendition, the orchestra is then created and the song is cut: ‘Ye mukhda hoga, ye antara hoga’ [this is the mukhda, this is the antara].

Even the singers do not know how their songs will eventually sound. If the song needs a flute or sarangi, they’ll call a musician. If the song is a rhythmic kind of song, they might call a dholkiwala, a dholwala. But the main orchestral sound is from sequencing.

Back then we used to record on mono tracks, which meant all the musicians were recorded on one track and the voice on another. The recording engineers were marvellous. They used to set up four microphones and the sound of many instruments went into this one input that would be mixed on the fly. ‘Yahaan flute ka solo aanewala hai’ [The flute solo comes here] and then in the next antara, there’s the sitar piece. The placement of the mics was precisely worked out, so when it was the turn of the sitar player he could be heard. The sound recordists knew the volume of which instrument had to be increased and when to do so.

I remember seeing Hariprasad Chaurasiaji standing at a microphone and around him sat a santoor player and a sarangi player. When the tune needed the flute, Hariprasadji took a small step towards the mic and played. Once his piece was done, he stepped back. That’s how it was done.

There were not many rhythm players, as far as I can recall. There was a dholak player who sat opposite me on the same level and a khanjariwala and manjirawala would sit nearby. We had a mic hanging over us and during the rehearsals, we were told: ‘Arey woh aap ka bayan baraabar nahin aa raha hai, thoda aise baithiye. Zara bajaana, achchha woh chanti theek nahin aa rahi hai, zara sa aage aaiye.’ [We can’t hear the bass tabla clearly, just move a little. Now play. We can’t hear the chanti, the high end of the tabla. Please come forward.] The Indian sound engineers were very knowledgeable about film music and the musical instruments. They knew how they should sound and how to record them correctly.

The soloists in big bands in America also stand up when playing and then sit down once their piece is over—by doing this they create the sound balance.

Nowadays we have multi-track recording and every bit of sound can be corrected—you can fix the tune, the pitch and whatever else you need to fix. It’s an entirely different process, but in the old days, the only person who could be re-recorded, with the least hassle that is, was the singer because he or she had been recorded on a separate mic.

NMK: I must share an insightful and telling quote about Lata Mangeshkar by Meena Kumari, who said: ‘If Lataji is singing, we don’t need to act.’

ZH: Because Lataji has already done everything! She has a three-minute song, and I have a one-hour concert, so I have time. The idea of projecting the whole ball of wax in a short amount of time is something very special. What’s important is the understanding of language, and the singer’s diction and ability to interpret the words in their many shades. When Lata Mangeshkar sang ‘Mora nadaan balma na jaane dil ki baat’ [My naive lover does not understand the ways of the heart], she had eight seconds to create emotion in that line. She is not thinking about it, she’s just doing it. Her remarkable ability was to interpret and express those feelings and sing in a manner that when Madhubala or Nargis parted their lips, the song appeared as though coming from them.

For me the heart of a good song are the words. They convey what the character is feeling and give expression to the emotions. This makes creating melodies on those words even more challenging. No one was as good as Majrooh Sahib in writing lyrics on pre-composed melodies. His words were beautiful, simple and straightforward—just what the tune needed.

Take Majrooh Sahib’s song ‘Mehboob mere mehboob mere, tu hai to duniya kitni haseen hai, jo tu nahin toh kuchh bhi nahin hai’ [My beloved, the world is full of splendour because of you, without you there is emptiness]. It’s beautiful. I remember that was one of Abba’s favourite songs. I asked him why, and he said the words fit the simplicity of the melody perfectly and that it all came together effortlessly.

Sahir Sahib also wrote on the tune, but it did not work as

well. But think of his wonderful ‘Aadmi ko chahiye waqt se darr kar rahe, kaun jaane kis ghadi waqt ka badle mizaaj’ [Man should fear Time, who knows when its temperament will change].

In the early days, the directors and the composers were knowledgeable about Urdu.

Many of today’s film composers have grown up in an English-speaking environment and therefore are not that close to Hindi–Urdu traditions. That said, it’s difficult for me to comment about the lyricists and composers today because I have not seen the recent films. I know that some people have worked as musicians in their formative years and are now composers, like Shankar–Ehsaan–Loy, A.R. Rahman, Salim–Suleiman, Jatin–Lalit, and Aadesh Srivastava who just passed away. They used to be rhythm players, piano players and guitarists. Of the older generation, Laxmikantji was a mandolin player and Pyarelalji a violinist before they became composers. R.D. Burman was a tabla and rhythm player. Composers who started off as musicians are definitely more experienced at scoring for films.

We must remember that ultimately composers have to provide music according to the director’s brief and compose a soundtrack that works within the narrative of the film. So, some of it will not be their best work, and the composers will be the first to admit it. But what’s interesting is that a composer like A.R. Rahman or the guys that I have mentioned can still manage to insert at least one gem of a song into a film. That song will show their pedigree as composers and what they could do if they were given half the chance.

NMK: During the time your father was composing film music, did you meet any of the lyricists he was working with?

ZH: One day when I came home from school, Amma asked me not to make a noise because my father was working. I peeped into the room where Abba was sitting at the harmonium. There was a gentleman with a pen and paper in his hand who was sitting near Abba. When I looked closely, I realized it was the poet/lyricist Kaifi Azmi Sahib. So they sat there—tune, words, words, and tune—all that was going on. They smiled at each other, and from time to time, they would ask Amma for some tea. They worked in that closed room for a long time and came up with a song.

One day I was telling Shabana Azmi, the poet’s daughter, about this and I said: ‘As a child I remember seeing your father in our Mahim home. I don’t remember the song Abba and he were working on, but I think the film never got completed and was finally shelved.’ I told Shabanaji the song went something like ‘Main toh khwaja ki deewani hoon’ [I am obsessed with the Lord]. She said: ‘You’re fibbing, it can’t be!’ I asked why. ‘My father was a communist; he would never write lines like that.’

But it was true, Kaifi Sahib needed work in those days and writing for films earned him money, so he could have been following a director’s brief.

NMK: Do you think your father liked working for films?

ZH: Abba enjoyed composing, but he belonged to a very different era of music directors. In his time, he composed the music, the lyricist wrote the words, and together they presented the finished song to the director. The director did not tell them to add this line and that rhythm. It was very difficult for Abba to accept that some guy who knew nothing about music was telling him the kind of music he should compose. I remember hearing that the star of a film wanted his songs to be sung by a particular singer and my father put his foot down and said, sorry, no. Abba was that kind of a guy and so he gained the reputation of not playing ball.

I was aware that some actors, including Dilip Kumar, Dev Anand and Ashok Kumar were knowledgeable about music, and so were some of the great directors like K. Asif, Bimal Roy and Raj Kapoor. In fact, I recorded some songs for a Raj Kapoor film, and from my personal experience, I could see that he knew about music. Of course, there were other film-makers who knew about music, but I did not know them personally.

NMK: In 1989-90, I met the gifted composer Sajjad Hussain, whom you mentioned, and like your father, he was clearly a man who did not compromise. You said he was your former neighbour in Mahim. Was he living close to your family?

ZH: Yes, if this is the building where we were—slightly off the main road—you walked to the main road and carried down a block and a half, and you’d find the Natal Building. That’s where Sajjad Sahib lived. The building is still there. One of Lataji’s gurus, Amaan Ali Khansahib, also lived in that building.

Sajjad Sahib was an uncompromising composer like Abba and Jaidev Sahib. They were vigilant about their work and proud of their music, and refused to change it in ways that did not fit their sensibilities. Sajjad Sahib wrote beautiful film songs that were challenging for a singer, and therefore more enjoyable, but he was not a team player and ultimately that’s what film-making is all about. You’re working with a director who has a vision of the complete movie in his head. You have to help him or her to create that film—you can’t impose your vision on someone else’s film. So, if they wanted an old-world sound, they did not ask Sajjad Sahib but went to Khayyam Sahib because he was easier to work with.

NMK: When you were playing the tabla for film songs, did you observe how the singers prepared for a recording?

ZH: Yes, I did. When a composer sat with Lata Mangeshkar, he sang her the tune on the harmonium, and she made some markings on the lyrics that she had previously written out in her own hand. Her markings created a map of the route that she was going to take through the song. That route highlighted certain notes, or which part of the song allowed her to take a breath—this line is this long, so I need to take a breath somewhere here—this is shorter, so that’s not a problem. Lataji marked up her lyrics in a few minutes. The whole city was there, the water stops, the lunch stop and where she would take a break. It was all laid out. It’s an incredible skill, and I know the singers of today use the same method too. The interesting thing is that this system of mapping is not standardized. All the singers have their own way of marking up the lyrics.

I also noticed that the composer rarely had to sing the song twice for playback singers, once was usually enough. They grasped the tune very quickly and were ready to record—this applied to many singers of the past like Lataji or Ashaji, but also to the current generation, including Sonu Nigam. They can sing the whole song straight through because they have mapped it all out and so follow the route and arrive at their destination.

NMK: Do you map your performance before a concert?

ZH: There’s a difference because I am improvising, but I do work out an outline. Within the parameters, I’ll navigate my way through as and how I please. It’s like being in a skating rink, you can go this way or that, or cut across, but you’re still in the rink.

For me it’s improvising—and that’s not so difficult. But playback singers have to understand the meaning of the words and grasp the tune that has been sung by a composer who himself may not be a very good singer, and who may not have conveyed all the subtle nuances of the melody.

NMK: Is there such a thing as purity in film music?

ZH: [irritated] Purity? That’s something I cannot come to terms with. If you’re doing film music, it is already a non-Indian form and you’re probably going to use Western instruments to play that music, so the concept of purity does not apply.

Take a composer like Sajjad Hussain Sahib. He was a fantastic mandolin player. I once heard him play with Abba in a house in Chowpatty—the way he played the mandolin, a small instrument like that, and for three hours. It was amazing to hear him. He was a superb musician. Sajjad Sahib’s three sons also play the mandolin. But when you speak of ‘purity’, remember the mandolin is not an Indian instrument. It is a European instrument, related to other instruments such as the lute and the oud. In any case, it is totally non-Indian. So film music has been played and continues to be played on a variety of instruments that are not all purely Indian.

NMK: We have talked about recording film music, what about the process of recording classical music? Say here in India or in the West.

ZH: That’s straightforward. It doesn’t really matter whether you’re recording in India or in

the US; it’s the same process.

What’s become increasingly problematic in India is to find a studio that has enough physical space for two or three musicians to sit together and play. Because it’s all on the sequencer, there is no longer any need for large halls. The music director sits in the same room as the soundboard and there is a small booth for the soloist or singer. This small booth is the only space available for musicians, so that’s a problem. Yash Chopra’s YRF Studio has a large room for musicians and there are a few other recording studios in Bombay and in Madras. Mehboob Recording Studio had a large hall but it has closed down.

Recording gets complex when you’re playing a different style of music, say jazz; otherwise, recording a raga with a lead instrumentalist is no different from a performance. When we make a sixty-minute CD, it takes about a day. And if something goes wrong, you don’t have to repeat the entire piece because you can cut and edit and do all that. In the old days, a recording of a two-hour concert had to be edited down to forty minutes—remember, an LP had only twenty minutes on each side? That was a big challenge because the music had to have completion and resolution, and the edits could not sound jarring.

I enjoy recording. It’s a creative process—it’s like going to the beach with an easel and canvas to paint the scene. You look at the horizon, the shades of the clouds, the sunset—and ignore the pollution. [both laugh]

The power of shaping things is the fun of recording. I can start off with one thought and end up with an entirely different one. In the old days, the one thought was the only thought and did not become anything else. To take the same clay pot and create different shapes is like waving a magic wand.

NMK: Was working on film music a good period in your life?

ZH: You must remember I was still in my teens, and somewhat taken by the glamour of cinema. I grew up on films; I listened to film songs and enjoyed them. To be part of the process was very exciting, to see how film music was put together was a whole new world to me. It felt as though you had entered a large hall and walked up to a gigantic screen and stepped into it. Here’s this car chase scene, and you were right there sitting in the back seat. Some months later when I would see the film and hear the background music, I smiled knowing that I was a part of it.

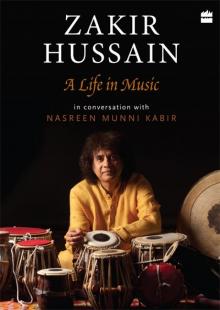

Zakir Hussain

Zakir Hussain