- Home

- Nasreen Munni Kabir

Zakir Hussain Page 10

Zakir Hussain Read online

Page 10

Take the Punjab gharana [tabla]; it has maintained close ties to the pakhawaj. We students have all had to study the ancient language and compositions in this system, and were even encouraged to take up the pakhawaj as part of our initial taleem [training] before we moved exclusively to the tabla. My father’s guru, Mian Qadir Baksh, was a pakhawaj player and it is said that a majority of the rhythm players in Punjab were Mian-ji’s students.

NMK: I believe your close friend Mickey Hart studied tabla with your father, and then you worked with him on the now famous album Planet Drum. How did that come about?

ZH: Planet Drum is basically a link in a chain of events. Mickey Hart and I had begun working together in 1974-75. The music ensemble that I started in 1973 was renamed the Diga Rhythm Band and Mickey and I produced an album called Diga. Warner Brothers released the LP in the mid-1970s. It was the very first world rhythm ensemble, and featured drummers from India, the USA, the Middle East, Latin America, Africa and other parts of Asia. No one had thought of doing this before.

The relationship between Mickey and me strengthened from that time, and we decided that we would find like-minded rhythmists from various parts of the world and see if we could somehow spark an interest in the importance of rhythm. This led to different attempts including the Rhythm Devils. But the spark really happened when the book Drumming at the Edge of Magic: A Journey into the Spirit of Percussion, which was written by Mickey Hart, Jay Stevens and Fredric Lieberman, was published in 1990. The book accompanied the album At the Edge, and in the book, Mickey explored the origins of drumming. There was also a chapter in it talking about my work, and where I came from, etc. The book was a huge success, and so was the accompanying CD. It had tracks by like-minded rhythmists from Nigeria, Brazil and Afro-Cuban traditions. This attracted interest in what we were doing as rhythm players, so we could record the album Planet Drum.

We all believed that this planet is a rhythm planet. So, the idea was to show that rhythm is in everything, and even the earth revolves around its axis at a particular rhythm; the solar system works in rhythm—the whole idea was rhythm.

Babatunde Olatunji, the senior statesman rhythm maestro from Nigeria, the Brazilian Shaman drummer Airto Moreira, and I got together with Mickey Hart. Each of us brought another rhythmist to the mix. Airto asked Giovanni Hidalgo and his wife Flora, a singer, to join us; Baba Olatunji brought Sikiru Adepoju, who was another Nigerian talking-drum maestro, and I asked T.H. Vinayakram from India. That made a very substantial group of people.

We co-produced and recorded Planet Drum. We did everything. The recording took only seven days. Mickey, the engineer Tom Flye and his assistant Jeff, and I threw ourselves into the post-production and a month later we emerged bleary-eyed with the PD master. When the album was released, it topped the world music category for some twenty-six consecutive weeks and sold almost a million records. At that point, the Grammy Awards did not have a category for world music. When Planet Drum was about to come out, in 1992, they introduced a ‘Best World Music Album’ award and we were the first to win it.

My father and guru, and his two colleagues, who were the holy trinity of the tabla, initiated this fight for drummers to be recognized, and to a certain extent Planet Drum fulfilled their vision. It is an out-and-out rhythm recording and as a percussionist myself, it is a well-deserved nod to the importance of rhythm.

Planet Drum was not a one-time project; it triggered a huge interest in rhythm and fanned the popularity of bass-and-drum-based hip-hop, rap and beat music, all of which came from rhythm-based music. As these forms started to emerge, rhythms became a very important element in a recording. It has now got to a point where most hip-hop and rap artists ask their music producers to send them a beat so that they can write their songs to a beat, and stuff like that.

Before Planet Drum, you did not have that kind of interest in rhythm-based music, and so it sparked this whole new way of thinking. In that sense, Planet Drum remains a landmark. And then The Global Drum Project followed.

NMK: In the mid-1970s you were involved with Shakti. The impact of Shakti was huge and certainly helped to further the sounds of world music. It not only had musical influences of the East and the West, but also of north and south India. I remember hearing the album A Handful of Beauty (1976), and its title so aptly described the music. Shakti is a real milestone.

ZH: The reason Shakti is a milestone, and of personal importance to me, comes from the fact that it opened the doors to the concept of world music. It was doubly sweet because the foundation of Shakti was laid at the same time as Planet Drum.

Shakti is unique and unparalleled in the universe of music and it was probably the first group of its kind to have explored, without limit, the one salient feature that is common in Indian music and jazz—and that is improvisation. There were earlier attempts that combined the two systems, but as far as I know, besides the LP Karuna Supreme, which released in 1975 and which Ali Akbar Khansahib, John Handy and I did, all other attempts involved composed solos that were written without spontaneous improvisation.

Shakti explored the idea of spontaneous improvisation. The advantage we had was that John McLaughlin, apart from being the most versatile guitarist of his time, was also someone who had studied the Indian system of improvising. He had learned how to play the veena, and our other team member, the violinist L. Shankar, had learned about jazz harmonies and had worked with that form. As we’ve discussed, working extensively as a teenager with Hindi film musicians, who played all kinds of Indian and non-Indian instruments, helped me. I was also given an insight into the jazz and rock world by my father who brought from his travels many records of bands like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and the Doors. I remember Abba had me take some piano lessons as well.

The most important fact was that we, the Shakti team, were young enough to allow for musical ‘sacrilege’, and so we could ignore the restrictions imposed on us by our respective traditions in the interest of finding a road towards oneness. Similarly, the connoisseurs at that time frowned upon interactions between south and north Indian musicians, but the advantage for T.H. Vinayakram, fondly known as Vikku, and me was that rhythms are universal. In addition, I had the good fortune of occasionally working with the great maestro Palghat Raghuji, and had also come across south Indian musicians working in Indian film music. I gleaned information that would help to overcome any barrier between Vikkuji and me. We were young and game enough, and fortunately away from India and critics or so-called well-wishers who would have been happy to give us negative advice—and so we were totally comfortable running amok on the taal road. [smiles]

There we were—four musicians from varied backgrounds sitting on a stage platform in Indian style, and with complete conviction, playing music that was never heard before—it was a totally positive offering. The energy of four as one was strong. We were confident that our musical statement would become valid and accepted as a road to traverse and that would eventually lead to what is now known as world music.

NMK: I’m sure it will come as a surprise to many that Hindi film music was an added help to you when creating music in later life. I suppose the fact that so many different instruments could be played on a song, and sound great together, must have broken down barriers. In a way, we could say Indian film music was early fusion music, involving Indian and non-Indian instruments.

But you were also saying some connoisseurs frowned upon the interaction between north and south Indian musicians. Could you expand on that?

ZH: The rhythm system in south Indian music is very organized. There is a standardized formula that lays down the way the transmission should take place. Every student studies this basic formula that uses maths as the seed idea of rhythmic improvisation.

In the north Indian system, the emphasis is more on the rhythm tradition being a language. It is therefore more of a storytelling process, so equal importance is given to the grammar and the maths enshrined in the rhythms. Because of this teaching styl

e, there is great emphasis in the north Indian system on an individualized approach to improvisation and this has created many points of view [gharanas] rather than a single standardized approach.

Personally, I thought it was a great fit to combine the teaching systems from the north and south—and so give tabla students a teaching process that incorporates all the important points of view [gharanas] into one coherent idea. I used myself as the guinea pig and found that it was a huge learning curve for me. As a result, a much-needed dimension to my musical expression has been added.

I must thank the great Palghat Mani Iyer, Palghat Raghuji, my dear friend T.H. Vinayakram, Shri Lalgudiji, Shri Balamuraliji, L. Shankar; the lord of the mandolin, U. Srinivas, and many others for helping me to imbibe, in a minuscule way, some of the salient features of south India’s rich musical tradition.

NMK: Can you talk about how much the north Indian masters influenced you?

ZH: I will try to give a very short answer to a very long and ongoing story.

I believe a teacher or mentor can instill in a tabla student all the ingredients and tools necessary for him or her to become technically efficient as a solo performer. But it is a near impossible task to impart all the improvisational abilities that would meet the potential demands that are made upon the tabla students when they accompany a lead musician. It is through assimilation that they must accumulate these skills—by listening, watching, memorizing and analysing. So, if they are able to find mentors, say an instrumentalist, a vocalist or a dancer to bounce off their ideas, they’ll reach a clearer understanding of their craft. This helps a tabla player to build confidence in the ability to cope with the demands of being an accompanist.

I had the good fortune of playing the tabla for Kathak dancers; I became an apprentice accompanist on one glorious occasion to Ali Akbar Khansahib, an apprentice accompanist to Ravi Shankarji and an accidental accompanist to the Kathak diva Sitara Deviji. All this happened before I was sixteen—a privileged student indeed—but it was not until I joined Ali Akbar Khansahib’s music college in California as a teacher, and became his accompanist that I really found my first instrumentalist mentor. It was then that I started to put my portfolio together in earnest.

The learning must continue. Reinventing one’s self is an ongoing process—being in the present with an eye to the future. My growth would have remained in the shadow of Ali Akbar Khansahib’s musical expression had it not been for the influences that arrived in the form of Shivkumar Sharmaji, Hariprasad Chaurasiaji, John McLaughlin and Mickey Hart. Shivji and Hariji were amazingly generous performers who were more than willing to let me try my wares on the stage and be my sounding board. It was my association with a number of these greats that has helped me create my tabla identity.

Accompanist tabla players are chameleons that are both expressing themselves and reflecting the ideas that the main artist wishes to convey. If they are successful at this, they’ll become the true exponents of all musical interactions. I am not sure if I will ever be that. But I must, in all humility and gratitude, say that hopefully I am what these greats envisaged, and that the lessons I’ve learned from them can go forward in the intended spirit. It has been a joy to learn about this wondrous art form from these fabulous practitioners.

NMK: In rereading what you’ve said to me, it is clear that your training and relationship with your father has been unmatched in your life.

ZH: It was very important. Look, I started off as his son and then I became his student, apprentice, colleague and finally a friend. We lived through many facets of a relationship. Yet it was obvious that he gave more than he got.

NMK: You don’t think he got anything back?

ZH: He may have, but I think he gave more. I was very selfish. I took. Maybe I could have helped him become more of a man of the world.

Whenever I think of an example of purity, I visualize my father. He was not of this world. He was not made of this clay. I remember he would never worry about things. There were so many times when we sat in the semi-darkness of the Akram Terrace flat in Mahim and Amma would say: ‘I only have a few rupees left. Kal bazaar kaise hoga? [How will we buy food tomorrow?] Abba would simply smile and say: ‘Don’t worry, God will provide.’ And sure enough, an hour or two later, someone would arrive at our door and tell him: ‘Tonight there’s an impromptu music programme by Vilayat Khansahib. They want you to play. Will you come? Here’s 100 rupees.’ In 1958-59, a hundred rupees was a lot and so that bought us food for the next few days.

Abba was a man of God. When he started playing with Ravi Shankarji, he decided: ‘He’s my brother. I’ll play with him and no one else.’ He refused all other concerts. He did not make a zillion rupees—that did not matter to him. What mattered to him was being where he wanted to be. That made him happy. He had the kind of personality, or purity, that you talk of when you describe your impression of meeting Bismillah Khansahib—someone for whom only music mattered.

NMK: I’m assuming you have accompanied Bismillah Khan?

ZH: Yes, I have. There was a man called Bipin Bihari Sinha, a concert organizer and a friend of my father’s, who asked me to play in Patna when I was about fourteen. I was too young to travel alone but Sinha Sahib promised my father that he would look after me. He was involved with a very well-known festival that took place at Dussehra, and still does. So, in 1965, I went with Sinha Sahib to Patna and played tabla with the musicians that he had invited. One year, I was accompanying Shivkumarji, and another year it was Pandit Jasrajji. At a private gathering I even got the chance to play the tabla for Begum Akhtar. Her regular tabla player, Mohammed Ahmed Khansahib, had to return home because of some family issue, so I was asked to play. After the evening’s proceedings were over, there was a gathering where she sang. Many musicians were present.

It was also in Patna that I first accompanied Bismillah Khansahib and then again here in Malabar Hill at a wedding of a very rich businessman. But the opportunities of accompanying him became rare because his son Nazim started playing the tabla for him, and there was another guy on the nagara. So, Bismillah Khansahib had no need for anyone else.

NMK: You mentioned earlier that you do not play at corporate events or at weddings, so was playing at this wedding with Bismillah Khan an exception?

ZH: In my early years as a musician I took every job that came to me. Did I tell you that as a young kid I once had to wait in the kitchen before we were led into the sitting room to play for some rich folk? That’s how it was sometimes in the old days.

I was aware of all these corporate events that took place in some hotel ballroom and were usually private gatherings for company clients and employees. They would book an artist to perform and then a lavish dinner would be served. At first it seemed that they were supporting musicians, giving them work. It then got to a point that these private events were in fact taking away sponsorship from public concerts because the corporate world felt they were already doing something, so there was less and less financial support for public events.

I was once in Calcutta for a concert, Heat and Dust had been released, so I was already a face, socially accepted by the higher echelons. I was invited to a wedding of a rich family. We were all standing around on a huge lawn and I noticed at the end of the lawn there was a stage and from a distance I could see some musicians playing. I could hear they were playing the sitar and the shehnai very well, so I drifted over there and found that the musicians were none other than Bismillah Khansahib and Vilayat Khansahib. Guests were walking up and down the lawn, some people were eating, kids were running around and most people were talking. I felt so angry and so sad. I had tears in my eyes that something like this could happen to these great musicians.

On that day, twenty-seven years ago, I decided that I would not play at weddings and corporate events. I would just do concerts. I don’t do concerts that are sponsored by tobacco or alcohol companies either. It’s just something I won’t do. But I do play for friends. For example, Sultan Khansahib an

d I played at Sumantra Ghosal’s fiftieth birthday because we’re close friends. We surprised him and played in Pooh’s [Ayesha Sayani] house. It was fun. But that’s a different thing.

NMK: Did you talk to Bismillah Khan about music or were you too young?

ZH: He talked and we listened. When he came to Bombay, he always stayed on Grant Road in a very Muslim-style old hotel. ‘Humko toh yahaan theek hai, khana peena achchha hai, do room hain’ [This place suits me, the food is good and we have two rooms]. He and his ten family members stayed in those two rooms. The organizers would suggest that he stayed at the Taj Mahal Hotel, but Khansahib would insist: ‘No, no, this hotel is fine. The food is good here.’ During his stay in Bombay, he would play at the IMG festival, the Nehru Centre, Shanmukhananda Hall and then return home to Benares.

I liked the sound of his shehnai. Whether it was the way he had the reeds or the way he controlled the blow into the reeds, I don’t know, but he created a very blissful and musical sound. His tonality remains unmatched. When you hear other shehnai players, the tone springs out at you. With Khansahib it flowed out and was a very sweet and pleasing, embracing tone.

The shehnai used to be part of the naubat or ensemble of instruments played at royal courts. Bismillah Khansahib took the shehnai from there and brought it to concert halls that had great status all over the world. That is something very special. That’s why Bismillah Khansahib is Bismillah Khansahib. We have not heard of any other shehnai player who has come after him.

Another reason why he became famous in India was thanks to the movie Goonj Uthi Shehnai, in which he played the shehnai. The film became a very big hit and he became a household name, just like the Taj Mahal tea ads helped to make me famous in India.

NMK: They certainly did! When we met in Pune recently, the man at the hotel desk asked whom I had come to see, and when I said your name, he got all excited and said: ‘Wah, Taj!’ [both smile]

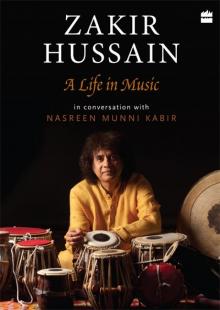

Zakir Hussain

Zakir Hussain