- Home

- Nasreen Munni Kabir

Zakir Hussain Page 9

Zakir Hussain Read online

Page 9

I must have done all right because on another occasion soon after that Maharajji had me accompany him in Patna. I played quite often for him. He is a very fine tabla player himself and understands how to bring the best out of his tabla accompanists. I learned how to accompany stories from Birju Maharajji and from Sitaraji. Just as the dancer plays all the characters in a story, the tabla player portrays all the characters through his instrument, sonically amplifying the expressive and emotional aspects of dance.

Sitaraji was a great storyteller, a kathakar, and it was a pleasure to watch her and accompany her through the telling of these stories. With Maharajji it was different, it was the joy of spontaneously trading rhythm patterns, and together arriving at the ‘sum’ (first beat of the cycle) with no prior knowledge of how we would traverse this tricky highway of taal. It was, and is, very intoxicating.

My association with Maharajji and Sitaraji lasted forty years and I consider myself fortunate to have had them among my many mentors, and it is with deep gratitude that I acknowledge their guiding hand in my growth as a dance accompanist. I mentioned to you that Sitaraji just recently left us in November 2014. These were cherished and enlightened encounters.

NMK: How wonderful to be in a position where your understanding of music can come from so many sources. I am no expert in music, but like many non-experts, I too can feel the effect it has on emotions. I am wondering if you have been moved to tears on hearing a particular piece of music.

ZH: It doesn’t necessarily have to be classical music. I’ve heard folk music that has moved me to tears.

We were judging a Saregama TV talent show, and Sonu Nigam was the anchor. That was the time when the judges were the decision makers and there was no voting through cell phones. We were filming this particular show in a New York studio and there was this singer from the Punjab province of Pakistan, and he sang this beautiful folk song. The song was all about the longing for home. It was so moving and so beautiful that I had tears in my eyes. I had forgotten that I was in front of the camera. I was a young man and I suddenly missed home. It was embarrassing but it happened. He sang so beautifully. So, it wasn’t Bade Ghulam Ali Khansahib’s thumri, ‘Ka karun sajni aaye na balaam’, Ali Akbar Khansahib’s Raga Chandranandan, Ravi Shankarji’s Hameer, or Vilayat Khansahib’s Bageshree that ended up moving me to tears.

*

NMK: We haven’t met for a while and you’ve been so busy in the past few days. Zakir, thanks for making time for our book.

Can we start today by talking about musical instruments? How long does it take to get accustomed to, say, a new tabla?

ZH: In the world of music, and especially when it comes to traditional music, haste is not a good idea. You need time to build a relationship with your instrument. The instrument’s spirit has to react and then things happen. You don’t just buy a new sitar today, get on to the stage tomorrow and start playing it. The sitar must come into its own. You have to play it for some months before you feel comfortable—ok, now I can play it on stage.

What do I bring to the tabla? I think it is openness and clarity, and that is what we bring to the audience. What I present must make sense, whether that involves a heart-to-heart interaction between musical instrument and musician, or zero hesitancy in the thought process, or not worrying about the parameters—your musical statement must be created with as much clarity as possible.

I am reminded of a lovely incident. Kishan Maharajji was about to go on stage when someone said: ‘Maharajji, have a great concert.’ He replied: ‘Dekhenge bhaiya, aaj tabla kya kehta hai’ [Let’s see, brother, what the tabla wants to say today].

It’s the same with all instruments—the guitar, piano, bass, or violin. You need to have a relationship with the instrument, because you want it to do your bidding. It has to accept you, and show you that it is ready to take that leap of faith with you.

For example, I need the tabla skin to have a certain amount of give—so when I hit it, it must respond and resonate in a certain way. The tone should have a certain amount of bass, treble and mid-range. The pressure of my hand is different from the pressure of someone else’s hand, therefore that impacts the thickness of the skin—how much extra skin must there be, so that it can bend in the way I want it to.

NMK: For those who don’t already know, the word ‘tabla’ comes from the Arabic ‘tabl’ which means drum, but there are, in fact, two tabla drums—the smaller one is made of wood and called the dayan (the right drum) and the larger deeper-pitched drum is made of metal and called the bayan (the left drum).

Making the tabla must be a very skilled job. Are tabla makers greatly appreciated?

ZH: I personally feel tabla makers in India don’t get their proper due, nor do they get the kind of monetary return they should. If somebody in America makes a guitar by hand for a famous guitar player, they charge between $12,000 and $20,000. Béla Fleck is a master of the banjo, and some of his banjos are worth $120,000. All musical instrument makers in India are not really compensated enough or given the kind of respect and status they deserve.

In my case, Haridas Vhatkar has been making my instruments and repairing them for the past eighteen years. He used to live in Miraj, near Kolhapur, and as a young man he came to Bombay because he heard me play. He decided to learn how to make the tabla, so he could make them for me. Sometimes the parts are made in machines and then assembled together by someone who has the ear and knowledge, while Haridasji does everything from scratch—he gets the buffalo hide straps, polishes and cleans the goat skin to get the rough edges out, etc. It’s all done by hand. The whole process can take weeks. The buffalo straps have to be soaked in oil to make them soft enough so that they can be pushed through the little grooves on the edges of the tabla and then tightened. All tabla makers sit on the floor and work—so all this pulling makes their backs go and it is murder on the hands. You can of course buy a standard tabla, which will not have even 10 per cent of the quality of Haridasji’s work. He has become the Steinway of the tabla!

I have put Haridasji on a stipend. So, if I’m gone for eight months, he does not have to worry, he will still have some money coming in. He came to America in July 2016 during my retreat, and repaired the tabla of forty of my students. He made a bundle and came back to India. [laughs]

NMK: Good for him! When I think about the different Indian instruments, the sitar sounds less melodic than the flute or the violin to me. Sorry if it’s stating the obvious.

ZH: One of the reasons why the sitar may not feel as melodious to you is because the flute is an out-and-out melodic instrument, and the violin is similar whilst the sitar is both melodic and percussive. Because it has this rhythmic ability, the sitar can very easily feel overbearing. When Ravi Shankarji played, there was great emphasis on rhythm, but that’s not what I noticed in Vilayat Khansahib’s playing. He was more into exploring the sitar’s melodic element. The rhythmic element came into his playing, but did not appear to dominate.

In the old days, there were no microphones and the instruments were not as finely made, so their resonance was very limited, therefore a more rhythmic style was played on the sitar. Listen to the old recordings, you’ll find the sitar playing was somewhat based on the way the Afghani rabab is played.

In instrumental music one style or school is called ‘rababi’ and the other is ‘beenkaar’. The ‘been’ is an ancient instrument from which the surbahar and the sitar were created. The rabab is a lute-like instrument, more prominent in Afghanistan, and from there came this style of rhythmic playing. If you Google a rabab recording, you’ll hear how rhythmic it is. They say that the sarod emerged from the rabab, but I’m not sure. I can’t trace that lineage, but a lot of the rababis eventually became sarod players, like Amjad Ali Khansahib, his father Hafiz Ali Khansahib, and Hafiz Ali Khansahib’s guru. On the other hand, Vilayat Khansahib and Ustad Allauddin Khansahib were from the beenkaar gharana.

It’s strange, but when I was a young tabla player and I heard Ravi Shankarji a

nd Ali Akbar Khansahib play a duet, the sitar sounded very pleasant to me and the sarod sounded very aggressive. I don’t know why. Later, when I started accompanying Khansahib and got to hear the sarod a lot more, the depth of that instrument emerged and I realized it had a much better balance of melody and rhythm. I became a fan of the sarod, but that happened only when I was about twenty-one years old. Before that, and maybe because my father was playing with Ravi Shankarji, I was a happy fan of the sitar.

NMK: What about the sound of the shehnai?

ZH: The shehnai is a very difficult instrument to play and can sound terrible if it is played badly. There was an in-joke among us musicians about a line in the song ‘Aap ke nazron ne samjha’. The line goes like this: ‘Har taraf bajne lagin saikdon shehnaiyan.’ [A thousand shehnais started to play all around us.] And we musicians would laugh and say: ‘Saikdon shehnaiyan bajne lagengi toh sar phat jaayega!’ [If a thousand shehnais start playing, we’ll get a crushing headache.] [both laugh]

NMK: Is it all about the instrument?

ZH: That would mean taking the artist out of the equation. To me this chain of thought has limitations. It over-conforms to the rules of tradition and does not allow for interaction between musician and instrument. There was magic when you heard Vilayat Khansahib or Bismillah Khansahib play. There are other shehnai players but has anyone heard of them before or after Bismillah Khansahib? So, is it the instrument or the musician? I have heard many fine sarod players, but their hands do not grab my heart and squeeze it like the music of Ali Akbar Khansahib.

The masters say that your relationship with your instrument should be such that the instrument will get down on its knees and ask you to do what you will of it, extract what you want—have control, command and mastery over the instrument. Then there is another chain of thought that believes that the instrument is just a modem for presenting the music.

That reminds me of a lovely incident. Ali Akbar Khansahib and Sultan Khansahib and I were once sitting in his classroom in California and he said: ‘Sultan, did you bring your sarangi? Will you play something?’ Sultan Bhai replied: ‘Khansahib, I’m sorry, but I have left it at the hotel. I just came by to say hello.’ Ali Akbar Khansahib insisted: ‘We have a sarangi in our music store, let’s bring it out.’

So, they brought out the sarangi and put it down. Sultan Bhai looked at it and said: ‘Khansahib, this sarangi is broken. It’s in a bad state. I don’t think I can play it.’ Ali Akbar Khansahib smiled and said in Urdu: ‘Sarangi agar theek nahin hai toh kya hua? Haath toh tumhara hai’ [So what if the sarangi is in poor condition? The hand is yours]. Sultan Bhai said, ‘Oh, my God,’ and rushed into a corner of the room, tuned the sarangi as best as he could and started playing.

My friend Mickey Hart, who is also a musicologist, happened to be there with his Nagra tape recorder and so he recorded Sultan Khansahib playing. Two years later we released the album and since then, Sultan Bhai and now his family have received close to $12,000 in royalties. My conclusion is it has to be the musician, not the instrument. [both smile]

NMK: What a beautiful story! [After a pause] When we hear you play, it sounds so electrifying and perfect. I cannot imagine that you make mistakes. Or do you?

ZH: Oh yeah, everybody makes mistakes. Mistakes are part of life, as real as living and breathing, but the whole point is to keep going. Try to reach the summit another time. When I made a mistake, it used to worry me, but not any more because I’m not looking at the mistake as a mistake. It’s another point of view—something that I can revisit another time. That mistake is another branch, another idea.

Life is a learning experience. You’re a student. You never become a master and you never will, so there’s no point trying. Do we ever find God? No. But many people seek Him. I mean, God could be the love of your life, or the best song that you’ve written, the best riff that you’ve played, or the companion that you’ll never leave.

I often hear young tabla players tell me: ‘Should I be playing Punjab gharana? But this composition from this other gharana is so nice too.’ I tell them: ‘There’s no such thing as wrong, it’s just different. That’s all it is. Use it in your playing. Don’t think of it as wrong. If you do, you’re limiting your experience.’

NMK: But I am sure you still strive for perfection.

ZH: I do. It motivates me to get up every day, it gets me on to the stage again and again—because if you’re not looking for something, what’s there in life? It’s part of the creative process. I always say music dies each night and is reborn the next day. ‘Ek shamma jali, parwana uda, taiyyar hui, taiyyar hua.’ The parwana [moth] will burn, and yet it will be drawn to the flame again the next day.

Perfection is something you’ll never attain. But it doesn’t matter if I don’t attain it, at least, I would have tried.

NMK: Your father heard you play over the years, was he generous in giving praise?

ZH: No, not at all. An occasional ‘hmm’. That’s pretty much it.

One night when I was a kid, I was sleeping in my room and must have got up to get a glass of water or something and I overheard Abba and Amma talking. He was saying to her: ‘Kabhi tumhara Zakir aisa kuchh kar jaata hai stage pe, ke main hairaan ho jaata hoon ke yeh kahaan se aaya.’ [Sometimes your Zakir plays in such a way on stage that I’m taken aback. I ask myself from where did this come?] I think Abba wanted to share his joy and his sense of pride with my mother. He did not want to say it to my face. I just happened to overhear him.

Abba was often very critical, especially when I agreed to certain projects—what is this? Why are you doing this? It’s not you. I tried to explain to him that it was all a learning process. I needed to see if it had anything for me. If not, that was fine and I’d just move on. I wanted to discover things for myself. If I was going to play with John McLaughlin, for example, I had to learn about jazz.

Abba never really stopped me from doing anything, but he wanted to make sure that I did not forget who I was, and that I had an identity and should not lose it.

NMK: Your father love experimenting too. It is well known that he was the first tabla player to record an album with the great Buddy Rich. Their groundbreaking album was appropriately called Rich a la Rakha. So, he must have loved jazz too.

ZH: Yes, jazz is a cousin form to Indian classical, as I’ve mentioned. Abba liked jazz and had many friends from the jazz world visiting him in Bombay.

NMK: I must quote a wonderful comment on your father by Mickey Hart: ‘Allarakha is the Einstein, the Picasso; he is the highest form of rhythmic development on this planet.’ Your father made history in so many ways, including changing the way tabla players were regarded in India, elevating their status.

ZH: That is right. Earlier tabla players were basically non-entities when it came to receiving any attention in a performance. Their names did not appear in ads, and LP and EP record covers did not list their names. When it came to their remuneration, as we discussed, it was a tenth of what the lead artist was paid. Of course, we had tabla ustads like Thirakwa Khansahib, Amir Hussain Khansahib, Pandit Kanthe Maharajji and Habibuddin Khansahib who were occasionally presented in a solo baithak, or had a twenty-minute solo performance at a music festival, but there was never any focus on tabla players as being an equally important part of a classical concert.

In the 1950s, there emerged three very important instrumentalists: Ustad Ali Akbar Khansahib, Pandit Ravi Shankarji and Ustad Vilayat Khansahib. We have discussed these masters many times in this book, and it was these same people who saw the merit in developing a dialogue-oriented performance with their accompanying tabla players—they believed in the potential appeal that this would have. And fortunately for them, the tabla players, whom we refer to as the holy trinity of our tradition—Ustad Allarakha Khansahib, Pandit Samta Prasadji and Pandit Kishan Maharajji—emerged around the same time.

They were magical tabla players. They were exciting to watch, they thrilled audiences all over India with their control of laya, ta

al, and impressive sound production and dizzying speed. They had an electrifying presence on stage and knew how to capture the audience’s attention. These great tabla players became the partners and preferred accompanists of the three great instrumentalists mentioned above. Together they created music of high energy and intensity whilst presenting a vastly entertaining interaction.

Suddenly there came a new-found respect for the tabla, and the recognition of its importance on the concert stage followed. In fact, audiences would demand to know the name of the tabla accompanist before buying a ticket; and so organizers sometimes hired one of these great tabla players even before booking the artist they were to accompany. Their solo performances became very popular, and thus elevated the status of the tabla and the tabla players.

We owe everything to these giants; without their existence and Herculean effort perhaps we, tabla players, would still be in the shadows. All their hard work made it possible for us to reap the rewards, both commercially and socially.

NMK: In terms of the tabla repertoire, did it always have one of its own?

ZH: When the tabla found its way into the world of classical music, it did not have its own repertoire to draw upon, and so it ended up adopting and transposing the pakhawaj repertoire as its source material. Most gharanas eventually moved away from the pakhawaj and came up with a language that was a hybrid of the pakhawaj and the local drums of the region where the tabla players lived. Punjab and Benares found ways to adopt more of the pakhawaj repertoire and develop a fluid technique to comfortably execute those compositions on the tabla.

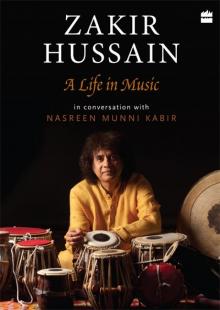

Zakir Hussain

Zakir Hussain