- Home

- Nasreen Munni Kabir

Zakir Hussain Page 7

Zakir Hussain Read online

Page 7

That’s the kind of a person he was. But when it came to the administration of his own world, he was probably more frugal than my mother. [both laugh]

NMK: It sounds like he had no sense of envy.

ZH: No envy at all. Perhaps one of the things that I have learned from him is to be content and satisfied with whatever you create and accept things the way they are. The other thing I learned from him was not to feel threatened. I can be competitive because I need to do things to express myself, but there was no need to feel threatened by the talent of others.

NMK: Ali Akbar Khan lived for many years in America. Do you feel he missed India?

ZH: I don’t think he missed India, but he missed certain things. He would call me and say: ‘Jhakir, kahin se shaami kebab le kar aao.’ [Jhakir, get me some shaami kebabs from somewhere.] He called me ‘Jhakir’, as he couldn’t pronounce ‘z’ because he was a Bengali and there is no ‘z’ sound in Bengali.

Only once did I hear him speak of something he wanted very much. He wanted to meet the singer Noor Jehan! And as far as I know, Khansahib never got to meet her. Noor Jehan did not come to America, and in later years he stopped travelling. This was a regret of his—never meeting Noor Jehan.

He used to listen to her old songs like ‘Chanda re chanda’ from a 1972 Pakistani film called Baharon Phool Barsao. There was another song that went something like: ‘Tere pyaar mein ruswa ho kar jaayen kahaan deewane log. Jaane kya kya pooch rahe hain ye jaane anjaane log.’ [Dishonoured in your love where do I go? Wherever I go, I am asked about you.]

I used to argue with Khansahib and say that Mehdi Hassan Sahib sang this song first. He would immediately say: ‘No, no, no! Noor Jehan sang it first.’ ‘But Mehdi Hassan Sahib has also sung it.’ ‘It was Noor Jehan.’

He liked her songs from Anmol Ghadi as well.

NMK: You mean the famous ‘Awaaz de kahaan hai’ (Call out to me, where are you) from Mehboob Khan’s Anmol Ghadi?

ZH: ‘Awaaz de kahaan hai.’ Yes.

NMK: Those eleven years, between the ages of eighteen to twenty-nine, were spent in his company. It was an undoubtedly an impressionable time in your life. Did Ali Akbar Khan become a kind of father figure for you?

ZH: He was not interested in becoming a father figure—that was the attractive thing about him. He did not behave like that even with his own sons. He had left India and so was not around his children who lived in Calcutta. His elder son Aashish knew him well, whilst the others were just teenagers.

I was a very young man, and he was about thirty years older, but he treated me as a colleague. How shall I put it? There was a compression of generations. He did not want to burden me or impose on me. Or make me deal with his great standing in music. The time that I spent with him was special—we played concerts and travelled to many cities. I taught at his music college and when my class was over, I observed him teaching his students. He addressed everyone as ‘aap’. He would say to me: ‘Aap kahaan the? Aap ne khana khaya?’ [Where were you? Have you eaten?] He addressed everyone with great respect and made you feel that it was you who was on the higher pedestal.

NMK: A sign of a very confident and cultured person.

ZH: Yes—making you comfortable but at the same time ending up making you very uncomfortable. [both laugh]

One day he walked into my house with Mary Johnson, a young American who had first studied the tabla with Abba and then with me, and said: ‘I have come to ask your permission.’ I was flabbergasted: ‘What, Khansahib?’ He calmly said: ‘We’re getting married, and you are her teacher, so I have come to ask for your permission.’ Now imagine that.

Mary became his third wife and it was she who was with him when he passed away in San Anselmo on 18 June 2009. He was eighty-seven. Mary Johnson Khan runs his college now. The then Indian prime minister, Manmohan Singh, wanted to bring his body back to Maihar and build a mausoleum in his name, but Khansahib’s family knew that he would not have wanted that. He was happy in America. He liked the simplicity and normality of his life there. Having said that, when he played his sarod, it was never a normal event—he could move the heavens. It was a sublime experience watching him.

I remember we were once playing in Patna. It was in October during Dussehra and it was very hot. Those big round white arch lights were directed on the stage, and it made us feel even hotter. Khansahib was almost completely bald and had a little hair on either side of his head. While he was playing, I noticed that his hair had started to grow. Suddenly there was this jet-black stuff on his head. I looked closely and what did I see? There were dozens of little insects and mosquitoes that had settled on his scalp and he was totally oblivious of them—he just went on playing. He was somewhere else.

NMK: Amazing. When Ali Akbar Khan passed away, in his obituary, Robert E. Thomason of the Washington Post (20 June 2009) included a fabulous quote by the master sarod player that I’d like to add here: ‘If you practice for ten years, you may begin to please yourself, after twenty years you may become a performer and please the audience, after thirty years you may please even your guru, but you must practice many more years before you finally become a true artist—then you may please even God.’

ZH: It speaks of Khansahib’s depth of awe towards this tradition.

In some ways, it leads the followers to believe it is hopeless. [laughs quietly] Here’s this person who is talking about fifty years and at the end you may even please God. At the same time, Khansahib himself was a professional musician at eighteen. But maybe he was talking about the kind of maturity you achieve over the years as your understanding of music grows, and your knowledge is more complete.

His statement leaves you wondering, but does not tell you something definite. ‘You may even please God,’ it is not you will please God. This quote is one of those gems that could hint at where we need to arrive. It is also saying that even if you do arrive, you are not there yet. It’s true that perfection may not exist, but what are you saying? ‘Don’t do music. It’s an uphill struggle and when you do get all the way up, a bear will eat you.’ [both laugh]

Ali Akbar Khansahib was a great teacher. But many old maestros did paint a picture of this art form in terms like: ‘Yes, you should do it, but it’s unattainable.’ Was that a good way to go about it? I don’t know. You need to speak of the importance of music, to tell students what an awe-inspiring tradition it is, but do you use such superlatives that make it an impossible task? Is this testing the will of the student, or trying to tell the student to go away?

If you are a teacher, you have a certain responsibility towards your students and so you tell them this is the kind of path you must follow, because this is going to get you near to where you need to be. That’s a positive approach. If you tell them it’s unattainable, you put cement on their feet and say I am going to drop you in the water and you’re going to sink, even if you try to swim.

My father never did that. He never gave me the impression that it was a mountain impossible to climb. He used to say: ‘Try this, do this, do that. What I see when I look at this mountain is not what you will see when you look at it. The peak may appear in a different place to me, but that’s ok. One step at a time and just go through this process.’

NMK: I was watching a beautiful interview of Ali Akbar Khan on his website, in which he said he never saw his father’s eyes because his own eyes were always lowered in Baba’s company. I found that so moving.

I suppose in view of the kind of taskmaster his father was, perhaps Ali Akbar Khan’s quote makes sense when he says he might never attain his goal.

ZH: Yet, the simplicity of the man was in wanting to meet Noor Jehan! So, which was the true him?

You have to realize that most of the things that ended up as quotes by Khansahib were spoken in the company of American students and followers. They looked at him with awe, and I understand that he felt the need to tell them how special and sacred this music was, but in doing so, did the description end up assuming inhuman proportions?

Believe me, if I had read that quote twenty years ago, I would have nodded my head in agreement and said: ‘Yeah, yeah.’ But my thinking over the years, I hope, has become more rational, more realistic. I think about how this art should be transmitted, as opposed to seeing it as a mythological impossibility.

I must tell you Khansahib was a man who rarely practised. A trait that we all appreciated was when he was performing on stage he never felt the need to please the audience. The entire musical fraternity around the world, including me, regard him as a musical genius, and I have noticed this about musical geniuses, including Khansahib—that one day his performance was a sublime experience that would get you talking for the next twenty years, and on another day it was a more ordinary experience. This was simply because he was not worried about tripping and falling on his face. How did that matter?

I am fortunate that I happened to be in the right place at the right time and that he asked me to work with him. He could have called a tabla player from Calcutta—maybe it was just a coincidence that he asked me—but in any case, I would have happily given my right leg, not my hand, to work with him!

I met my wife Toni in Khansahib’s Fairfax house.

NMK: Was your wife, Antonia Minnecola, a student at his college?

ZH: Not when we first met.

We’re talking about the time when the American music world was going through a ‘discover India phase’. Toni’s best friend Judy [Lynn McDowell] was working with Michael Butler, the producer of the rock musical Hair, and they were considering producing a musical with an Indian theme. So, Judy had gone to meet Ali Akbar Khansahib and the college director Jim Kohn to discuss the possibility of collaborating on the musical.

Later in the summer, Judy invited Toni to come to LA where a student from Ali Akbar College, who was writing songs for the musical, suggested they all go together to the college since the autumn session was about to begin. Toni attended a concert at the college and sat in on some classes. Judy was going to meet Khansahib again, so Toni accompanied her to Khansahib’s home, with the intention of asking him whether she could join the college. Toni had been attending a few classes at the Manhattan School of Music right before coming to California. I happened to be at Khansahib’s house that evening and that’s where we met. I think it was sometime in late September of 1971.

Khansahib’s son Aashish and I had a sort of fusion band and Toni came to hear us play at a club that same night. Khansahib had given her permission to study at the college, so she stayed on and Judy left. Toni began studying Kathak and the required vocal, taal and theory classes, and over the following months we kept running into each other. Eventually I asked her out.

I could not afford to take her to a nice restaurant, so we went to Jack in the Box and then to Sausalito, which is about an eight-mile drive from San Rafael. We had ice cream there, watched the full moon and walked along the bay. It was a very special evening filled with a sense that something great was making its way into our lives.

We became an item, but were not fully committed to each other. We lived together in different places and, finally, in 1976, we found a place where we could stay more permanently and it was there that we had our nikah.

NMK: So you got married in the States?

ZH: We had three marriage ceremonies in the US. The first was a civil marriage on 22 August 1978, then a church wedding on 23 September, which Toni wanted, and on 11 November we had a nikah ceremony, which Abba and Amma wanted.

Toni’s mother did not come to California for the nikah because it was too soon after the church wedding, and so Ravi Shankarji gave Toni away. Toni’s father had passed away many years earlier. My father was there and Ali Akbar Khansahib was a witness, so this very interesting little wedding took place in San Anselmo.

NMK: When did your parents first meet her?

ZH: Abba met Toni around the time when we were living together. She went to New York in the summer of 1976 to study with him and to look after him. They knew each other from that time, and things were fine. My mother first met Toni when she came to India to further her dance studies in the winter of 1974-75.

NMK: Do you think your parents would have preferred that you had married an Indian?

ZH: As you can imagine they thought I could have the pick of the crop. There was a guy who owned beedi factories in Bangalore and who wanted me to marry both his daughters because the sisters did not want to be separated! My parents imagined Zakir inheriting a beedi factory. [laughs] There were stories like that about possible brides, but somehow Abba was convinced that my marrying Toni would not come in the way of my music.

We were very young when we got married. I was about twenty-seven. Toni had just come to know Indian music, and I had just come to know the West, so we helped each other understand the other’s world. Through her I could understand what America was all about. Toni continues to be a sounding board for me like Amma was for Abba. My way of thinking has a lot to do with our conversations over the years. She knows how to support me with the right amount of smiles, and the right amount of seriousness. She encourages me to take bold decisions and has shown even greater recklessness than me in abandoning everything to pursue music. She was instrumental in my getting involved with all kinds of music. ‘Play music with this guy, work with him, you must hear him, you must hear her.’ My work with Charles Lloyd, Edgar Meyer, Béla Fleck, or Alonzo King LINES Ballet is all her initiative.

Toni was very involved in Indian dance and studied Kathak with Sitara Deviji for nearly thirty years until Sitaraji’s death in November 2014. My wife was a very devoted student. And instead of making a name for herself, she devoted herself to our daughters and to me.

NMK: So Toni holds the fort?

ZH: She always has. It was her energy that allowed us to set up our record company, Moment Records, in 1991. She co-produces the albums with me and as the art director, she writes and edits the liner notes and the artists’ bios besides overseeing the business side of things. I have no clue how to pay taxes or bills.

Toni has co-produced all my American and European tours from 1986 to 2008 until I started working with IMG Artists Ltd. Toni is dedicated to bringing the right focus to my music, and to Indian classical music. She’s my best friend, best critic and best support.

NMK: Was her family happy to accept you?

ZH: They were fine. I had spent so much time in America so it was easier for them. There was no language issue. It was initially very difficult for Amma—the first hurdle was the language—she could not communicate in English. So, that was difficult but my wife learned a little Hindi. Amma eventually realized that Toni was the best person for me, and she was in fact more Indian than an Indian wife my mother might have found.

You know my work takes me away from home a lot. And that’s not always easy. In my struggling days, I would go to Europe for a concert tour with Hariprasad Chaurasiaji and once that was over, there would be an eight or ten-day gap before Shivkumarji’s tour would begin. I could not afford to go back to the US for ten days, because it was more economical for me to stay with my sister Khurshid Apa in London. Biding my time in London meant being away from home for a longer period and that was very difficult for the family. I remember when Toni was pregnant with our elder daughter, Anisa, I went to India for the concert season and then to Europe with Shivji and Hariji, and when I came back, Toni was very pregnant. That’s how much time had passed. A similar thing happened when our second daughter, Isabella, was born.

NMK: You’re mobbed after every concert, and if you are spotted in a public space, people instantly crowd around you. How do you deal with your stardom?

ZH: Stardom? That’s not my problem. That’s an image others have created. Down the line, it will be over, so why worry about it? I don’t want to be caught up in a world that’s a passing breeze. I often quote the kahawat [adage] ‘Every dog has his day’. Perhaps I am the dog today. I could get used to the adulation and love, but five years down the road, I won’t have it

. So, I am going to have to get unused to adulation.

Sometimes Toni and I giggle about the attention I get. She knows that I don’t really care about it and she is not the type to let it affect her either. I remember we were once at a dinner in Venice where Sophia Loren was a guest. My wife loves this fine Italian actress, but it would not occur to her to cross the room and shake hands or take a picture with the star. She was just happy being in Sophia Loren’s proximity.

NMK: How do you react to fans and the selfie mania?

ZH: It happens all the time. I don’t mind it. This morning at the airport, the guys who look after the trolleys, the security guys, and the customs officers all wanted pictures with me. And I obliged. There were some passengers who wanted selfies too. I was in the train heading to my terminal at the Dubai airport, and the train passengers wanted photos. It’s okay.

NMK: Have you wanted to take a selfie with anyone?

ZH: Oh God! Maybe some fellow musicians, and of course my granddaughter. I’ve done selfies with her. For instance, I was performing at a concert yesterday with Shankar Mahadevan and Louiz Banks, and they were taking photos and stuff. My cellphone was off and in my bag. [laughs]

NMK: I believe you were voted the sexiest man in India by the female readers of an Indian magazine called Gentleman in 1994.

ZH: I thought that was very funny. The magazine team came to see me and wanted me to wear all these suits and jackets and Western clothes and feature on their cover. I think they were equally shocked and surprised that I won the greatest number of votes because they had assumed the winner would be Amitabh Bachchan. I think the result must have been a downer for them, because they weren’t going to get the kind of publicity they wanted from the poll result. [both laugh]

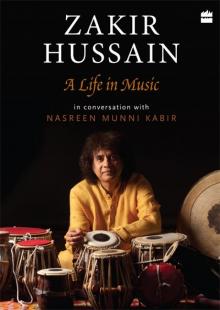

Zakir Hussain

Zakir Hussain