- Home

- Nasreen Munni Kabir

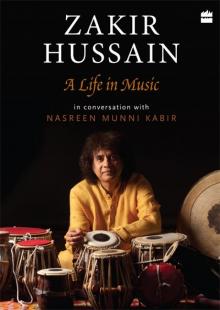

Zakir Hussain Page 8

Zakir Hussain Read online

Page 8

NMK: You’ve lived in America for decades now, and currently there is a growing anti-Muslim feeling there. Did you sense a change in attitude towards you?

ZH: I give credit to the vast majority of Americans whose thinking, I hope, has not been altered by what’s happening in the US now. That’s the way I see it.

I work in a world dominated by musicians and creative artists who don’t think twice about who prays in a church, mosque or temple. That has never been the issue. The same applies to artists in India.

We are going through a very tense time in America. But, generally speaking, when you live, like we do, in a place like California, you live among a diverse population, and I believe this makes for a more progressive and tolerant society.

Coming back to your question, I don’t feel personally discriminated against as a Muslim in America or in India or anywhere else in the world. Is this a defence mechanism? I don’t know, but I have never felt under scrutiny. The kind of environment I inhabit is sympathetic to the person that I am and is totally supportive of what I do.

You know, in the summer of 2016, I got a call from the White House wanting to give me the President’s Medal of the Arts. But there was a new rule that non-Americans could not receive the medal, but I was nevertheless nominated.

NMK: Talking about awards, I hear the San Francisco Jazz Center gave you a Lifetime Achievement Award on 18 January 2017. How was the event for you?

ZH: My God, it was fantastic! It was more than I could have ever imagined. There were four days of celebrations and an incredible gala. The dining room was full and every chair was taken. There were about 900 invitees. There were speeches by Nancy Pelosi and the mayor and many community leaders.

And then, surprise-surprise—my daughter Anisa made a five-minute film on me that was shown there, and in which many great musicians commented on my music. I didn’t know she was making the film and it was like wow! In her film, many musicians, including Herbie Hancock, Vijay Iyer, Eric Harland, the music director of the San Francisco Symphony Michael Tilson Thomas—each a master—talked about me. Other great musicians like Joe Lovano, during his musical offering, made generous comments. It was so moving. Anisa had also interviewed Charles Lloyd who spoke about a concert at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco where we had played together and which was billed ‘The Sacred Space’. This was just after 9/11 and the promoters were scared that people would not come to the concert out of fear of crossing the Golden Gate Bridge, thinking that somebody was going to blow up the bridge. Charles Lloyd said: ‘I was talking to Zakir about it, and Zakir very quietly said: “Music should be used for building bridges not destroying them.”’ Listening to Charles Lloyd, I realized that we are all learning from one another. Even though they are masters, they are also looking for knowledge and validity and recognition of being on the right track.

When I thanked everyone at the event, I said I had been given a pat on my back, but it did not mean I had arrived at the end of my journey. I have to take the next step. I suddenly remembered the Robert Frost line ‘Miles to go before I sleep’.

The whole event was very loving and emotionally charged. And after the film’s screening, my dear friend Mickey Hart presented the award to me and made a speech. It felt very surreal, and I was not sure whether I was awake or asleep, or in a Fellini movie! It was quite an experience. It reminded me of being in a room in our Mahim house, playing the tabla and peeping through the open door to see whether Abba was watching. And if he were watching, would he react and say something like: ‘Do this, or do that.’ A reaction from him was in some way a confirmation that I had got through to him and he liked what I was playing. That’s how I felt during the event. All these people were talking and I was in this room, doing all these things, and hoping that these great masters would accept what I had done and show me what to do next.

NMK: This must not have been the first lifetime achievement award that you received?

ZH: It was the first that came from that world. My main act is traditional Indian music and there is this cousin form, jazz. It is a whole world in itself, it has a life and tradition. A different protocol governs it. For them to accept this guy from another part of the world and embrace him as one of their own is a landmark moment—that Indian music and jazz have some distant relationship and it is not necessary to be apart—and instead to cross that bridge.

NMK: Were you the first Indian to receive this award?

ZH: Yes. But it’s just a pat on the back. To me it meant that I am on the right path and the place where I’m heading is where I should be going.

NMK: I browsed the SF Jazz Center website where the gala in your name was widely publicized. I’d like to add a quote by Herbie Hancock that appears on their website: ‘Everybody wants to play with Zakir Hussain. He’s amazing. He is able to transcend cultures and national borders.’

And you certainly have done that, and along the way you must have met and worked with many world musicians. Is there an encounter that left a deep impact on your playing?

ZH: For me the idea of rhythm as a multilayered entity was not very clear. I did not think of the tabla as providing a multi-sonic experience and I was just very happy to take the information given to me and whip it out on the instrument and have people applaud.

When I started playing concerts, the idea of exploring the instrument—of discovering various parts of the skin of the tabla, the right corner, the left corner, the centre, using the middle finger, the pinkie, the thumb, or just the palm, discovering how the tones change; and what kind of harmonics they suggest—all that was not part of my performance until I got talking to an extraordinary Latin jazz percussionist of Afro-Cuban tradition called Armando Peraza. I met him when our band Shakti was touring with another group led by a guitar player named Carlos Santana.

NMK: You say these names so casually! Santana, wow! [both smile]

ZH: Well! We were travelling together and performing every night. This was around 1975-76. We [Shakti] used to open the show—the guitar player John McLaughlin, the violinist L. Shankar, the ghatam maestro T.H. Vinayakram and myself—and Carlos Santana and his band took over after us. At the end of the show, the drummers from both bands got together for a jam session on stage. Drummers can easily jam because rhythm is universal. After the concert, we would all go and have dinner somewhere or have a glass of wine.

During the first two or three shows, I noticed that Armando played his solo with five conga drums in front of him. The biggest one is called the tumba. When he played with Carlos Santana, he just provided the rhythm. But here it seemed to me that he was playing a song on his drums. You could hear different tones, you could hear melody, the kind of melody that you hear a guitar produce—there were so many melodic structures happening. And if you looked around the stage, there was just this one guy playing. I was very intrigued—this was amazing. I could see he was not treating the drums as only a rhythm voice, but he was coaxing as many sounds out of them as he could—exploring, cajoling, squeezing. ‘If I play you here, come out and let me hear your reaction.’ Listening to him was like a symphonic experience in rhythm.

Later when I spoke to Armando, I said with great enthusiasm: ‘Wow! You play all those rhythms and a melody on your drums.’ He said: ‘Melody? I am not playing a melody. No, I’m just talking.’ Then he hummed a rhythmic sound, added some Spanish words, then some words in an African language, and finally he moved it all around to English. Suddenly it was a song. It all made sense to me—and it sparked this whole new idea in my head, to take my tabla, which had all those inherent possibilities, and somehow extract that kind of information and perform it for the audience. It was an incredible revelation.

The basic process started back then. It took me a while to figure it all out, but that’s what I do now. In those days, you did not do that on the tabla. Because the tabla has tones, at times it can sound like some melodic stuff is happening—you can converse with a vocalist, or players of the flute, sitar and sarod—not just rh

ythmically but also melodically. But this was not part of our job description. As a tabla player, the job was to play and let the lead musician do whatever he was doing. When he looked at you and his eyes said: ‘Ok, play a little,’ you played and then pulled back.

I revelled in the fact that I had found something very special. Armando Peraza made me understand the harmonic and melodic ability of the tabla. He planted that seed. Isn’t it strange how you have a tradition ten thousand miles away and it somehow fits like a glove with a tradition that belongs to another part of the world?

NMK: Many people talk about Indian music’s influence on jazz, but it sounds like it works both ways. As you say, it’s a cousin form.

ZH: Yes. It was after talking to Armando that I realized that Raviji and my father were doing more or less the same thing. Raviji had found a way to turn Indian music into an entertaining art form. He lit that fire. On stage, you could see his ability to charm. When he and Abba played together, they conversed with each other like two jazz musicians. In earlier times, this was not something that Indian music was all about. It was about the main guy and everyone else just following.

NMK: I saw your father and Pandit Ravi Shankar playing in Paris in the 1970s. Concerts themselves have this strong visual element, and that evening, I remember we the audience took so much from their physical presence—the way they commanded the stage, the way they sat, the way they held their instruments, the way they smiled at each other. They were conversing just as you’ve described. A great sense of complicity was established between performer and audience.

ZH: Had you seen Ustad Vilayat Khansahib or other great sitarists on stage, you would not have found that kind of interaction. They were unaware that musical conversations would appeal to the audience. But Ravi Shankarji understood that.

I think the way Indian musicians communicate on stage with one another today has a lot to do with Ravi Shankarji and Abba starting those musical conversations back then.

NMK: We have spoken about your playing tabla with numerous instrumentalists. I am sure you have accompanied many vocalists too. Am I right?

ZH: Well, this is the bane of tabla players who become a little well known; we are rarely booked to play with vocalists. In earlier times, I’ve played the tabla for many singers, including Nirmala Deviji, Shobha Gurtuji, Kishori Amonkarji, Ghulam Mustafa Khansahib, Bhimsenji and Pandit Jasrajji. As a twelve-year-old, I played with Pandit Omkarnath Thakurji.

I used to go to Walkeshwar every Sunday to Bade Ghulam Ali Khansahib’s house and be available to play rhythm for him. Khansahib’s wife considered my mother as her daughter. So they thought of me as a grandson, and the order conveyed to my parents was to send the grandson over on Sundays. My father understood the importance of it and said I should go. I was not hired to play tabla for Khansahib, he just wanted me around to soak in whatever was going on. Sometimes he would have visitors over, and at other times, he would just sit talking to his wife or to his younger son Munawar Ali Khansahib. If the mood was upon him, he would start singing, and then my job was to play the tabla. The whole idea was that I should understand that world and learn what I needed to know about vocal music, to get the tools that I would need in the future.

When I went to Calcutta for the first time, I was instructed to go to his house before being taken to where my father was staying. A Mr Das picked me up from Howrah Junction Railway Station and took me straight to Park Circus where Bade Ghulam Ali Khansahib was living. I paid my respects, and he talked to me for a few moments. Of course, his wife, whom I called Bari Amma, gave me a big hug and something to eat and then I was sent on my way to Abba.

Khansahib lived in Calcutta before moving to Bombay. Calcutta was a great centre for music and arts in those days and was home to many musicians. Sometimes Abba too would stay there for five weeks at a time, playing concerts all around the area, in Malda, Sealdah, Bardhaman and Kharagpur. Concerts would be held in Calcutta itself. There was the Park Circus Conference, Dover Lane Music Conference, All Bengal Conference and Uttarpara Conference.

When Bade Ghulam Ali Khansahib was once visiting Bombay, the great singer Ganga Bai convinced him to move here. She was living near Opera House and helped Khansahib to get a place in Walkeshwar.

NMK: What kind of person was he?

ZH: He was totally immersed in music. He appeared to be in a cocoon of sonic beauty. To see an artist so involved in his expressive mode is something. Time had no meaning for him. If you wanted to be a part of his music, you sat there and took what was coming at you. The expression and emotionality of his singing triggered a reaction in the people around him. That was probably when I first learned about the rasa element in music—to hear how love, longing, sadness, melancholy and devotion are expressed.

Just as Abba had been sent to Ashiq Ali Khansahib to understand how the emotional content is expressed through the voice, that’s what I was learning in the presence of Bade Ghulam Ali Khansahib. I think it helped me to become a more expressive tabla player. It may not have helped me at that point in time, but later I could use it and decipher it in my own way. You know how it is, you hear something and only later do you realize what it really is. I found accompanying a vocalist very stimulating and challenging.

I have also had the honour of playing the tabla for other wonderful singers, including Girija Deviji, Nisar Hussain Khansahib, the great Sahaswan-gharana singer. And in the 1980s, I organized some tours for Pandit Jasrajji in America and travelled with him. We have played together in Bombay and Pune and in other cities as well.

NMK: Why is a vocalist more effective than an instrumentalist in expressing emotions?

ZH: Because he or she is singing words and words add weight to the emotional experience, even though the lyrics are minimal in classical singing. I’ll give you an example: ‘Nahin aaye sawariya ghir aaye badariya’ [Though my beloved has not come, the dark clouds are here]. Those few words let you understand and feel the melancholy, the sadness and the longing. The singer may sing that one line for twenty minutes, but in those twenty minutes the singer has fifty different ways of expressing complex emotions and fifty different ways of subtly adjusting rhythm. As an accompanist, you can help the vocalist lift the performance to another plane for the audience.

NMK: Your analysis is so clear.

ZH: It’s not an Archimedes-type discovery. It’s just very logical. That’s why most tabla players have to learn compositions that are sung to understand the rasas at play, depending of course on the composition.

NMK: Sorry if I sound naive, but does an instrumentalist always aim to emulate the human voice?

ZH: We are told that the original music is vocal music and musical instruments were made to accompany vocal music or emulate it, and that’s what instrumentalists try to do.

The intricate possibilities, however, of the voice that a very special singer can produce, the combinations or permutations of notes, are difficult to replicate on the sitar or sarod. The sitar has an easier time playing certain things, but the sarod does not, and that’s why it’s very difficult for some sarod players to transpose some of the sitar elements on to their instrument.

That’s why Vilayat Khansahib and Ali Akbar Khansahib were unique instrumentalists because they came the closest to emulating vocal music. I must also add that they spent much time with vocalists. Vilayat Khansahib hung out with Amir Khansahib and when Ali Akbar Khansahib was a court musician in Jodhpur, he spent time with all the baijis—Gauhar Jaan, Siddheshwari Devi and Akhtari Bai, and also Faiyaz Khansahib—all those great singers.

I remember Ali Akbar Khansahib saying that he had accompanied Faiyaz Khansahib. And so had found a way of transposing those voice qualities on to the sarod, which is even more difficult than doing it on the sitar. Because the sitar has frets, you know where the notes are. But the sarod has no frets, so you’re guessing where a particular note is. Despite that, Khansahib was able to transpose the human voice on to the sarod—no sarod player before him had ever done that. And t

he same goes with Vilayat Khansahib. No sitar player came close to emulating the human voice on the sitar in the way he did—the taans and murkis and khatkas and so on. Sometimes he would sing a melodic combination and then execute it on the sitar. You could hear it, it was right there. That is why Vilayat Khansahib is credited as having created the ‘gayaki ang’ style [suggestive of the human voice] for the sitar.

NMK: What skills do you need when playing tabla to match the footwork of say a Kathak dancer?

ZH: It’s a unique and exciting challenge for any tabla player—it’s a give-and-take situation. Unlike instrumental and vocal accompaniment, here the tabla player plays a dual role—that of a soloist and a lead voice of the nritta, pure dance, and at the same time is a support to the storytelling sections of the Kathak dancer’s performance. To be a good accompanist, a tabla player must have a working knowledge of the repertoire and the ability to instantly transpose and execute the dance language on the tabla.

I was fortunate that in my teens I had played tabla for Kathak dancers in Bibi Bai Almas’s home—we talked about this. I also spent time in the company of the great Sitara Deviji and her brother Chaube Maharajji. Much of my knowledge of dance comes from these two stalwarts. I was twelve years old when I performed for Sitara Deviji for the first time, and it was through her that I had the opportunity of playing for Birju Maharajji.

A festival of music and dance called Sur Singar Samsad was held in Bombay, and Birju Maharajji was to dance there with Pandit Samta Prasadji as his accompanist. As it turned out, Samta Prasadji’s flight was cancelled. Hence, he could not make it to the show. So Maharajji called Sitaraji to suggest a tabla player, and she decided to take me along. We went to Birla Hall and she introduced me to Maharajji. I was about fourteen or fifteen at that time and I must say that Birju Maharajji did not even ask her why she had brought a schoolboy to play tabla for him. He trusted her and gave me his blessings. Perhaps it was because my father had accompanied him when Birju Maharajji danced on my fourth birthday. That may have had something to do with his accepting me.

Zakir Hussain

Zakir Hussain